These days, supplement shelves are filled with all kinds of different products based on plants. Tinctures, teas, whole plant preparations, standardized extractions, phytopharmaceuticals . . . but what’s the difference between them? These are the most common types of herbal extracts you’ll encounter, and they all have their own unique properties and uses.

Each of these extracts has a different level of strength in the body, with phytopharmaceuticals nearing the potency of conventional drugs. We’re often taught that stronger is better, but is that true for herbal extracts? By understanding the three main categories of herbal extracts, you’ll learn when it’s best to use each type and whether choosing the strongest extract is always the smartest option.

In today’s blog post, you’ll learn:

- What whole plant, standardized, and phytopharmaceutical extracts are

- The pros and cons of each type

- When it’s the best time and place for each extract option

- Why stronger is not always better when it comes to herbal medicine

- The power of constituent synergy and how it’s lost in certain preparations

Table of Contents

What’s the best way to take your herbal medicine? Is it infusions, decoctions, tinctures, tablets, capsules, standardized extracts, or super concentrates? With so many products on the market these days, it’s no wonder people feel overwhelmed, confused, and misled by powerful supplement companies often focused more on profit than providing the best and most effective form of herbal medicine.

Today, we’ll explore the different forms of herbal extracts available on the market, what they are, their differences, and whether there’s one form that’s better than the others. More specifically, we’ll discuss if it’s better to take an herbal extract stronger than what’s possible to prepare in a home kitchen, pharmacy, or even lab environment as an herbalist.

Sometimes it seems like our current culture always views stronger or more as better. From that perspective, the more concentrated an herbal extract is, the better it will work. But is that necessarily true? In the world of herbalism, is stronger always better?

By looking at the three main types of herbal extracts on a deeper level, you’ll find the answer to this question as well as when it’s the best time to use each.

Whole Plant Extract

Whole plant extracts are the types of extracts most commonly used by herbalists. This category includes any type of extraction that represents the whole plant, whether it’s powdered herbs mixed in water or packed into capsules, steeped in cool or hot water as an infusion, simmered on the stove as a decoction, alcohol-based extracts, infused oils, or any other method that uses an herb in its whole form to prepare herbal medicine. While tinctures and water-based extracts are not exactly consuming the whole herb (like you would as a powder), they still represent a full-spectrum of the plants chemical and medicinal properties.

Extracts made with the whole plant captures the plant’s chemical composition as it exists in nature. As herbalists, we are merely drawing the plant’s chemistry into our chosen menstruum—whether vinegar, alcohol, or water, or a mixture of them. By extracting the plant in its natural form, you receive the broadest biochemical spectrum of the herb possible.

To make sure you’re extracting the herb’s biochemical constituents when making a whole plant extract, you need to have at least a beginner’s knowledge of plant phytochemistry, such as understanding the chemical compounds present in a specific herb, the chemical categories, solubility range, and selecting the right menstruum to extract them. For example, herbs rich in tannins, like Red Raspberry (Rubus idaeus), extract best in water, while volatile and aromatic herbs like Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) yield stronger medicine when extracted with higher percentage alcohol. The more precise your knowledge of a plant’s chemistry and the solubility of those chemicals, the more effective your herbal preparation will be.

The most common method for preparing whole plant extracts is to tincture them, which involves using water, alcohol, and sometimes glycerin to optimize extraction (glycerin is typically added to herbs with a high tannin content to prevent them from precipitating out of solution). When stored correctly—cool temperatures, sealed properly to prevent oxygen exposure, and keeping them away from direct UV exposure— these extracts have a long shelf life, making them an ideal method of preparation and represent a holistic approach to preparing herbal extracts. Indeed, the proper ratio of alcohol and water generally can extract most (but certainly not all) medicinal plants very well.

Whole plant extracts have been effective since the dawn of herbal medicine. For millennia, people have infused and decocted medicinal herbs in water, and more recently, have preserved their medicinal value by extracting them in alcohol.

One reason whole plant extracts are so effective is the principle of constituent synergy. This means all the plant’s constituents work synergistically to deliver its medicinal properties. This is in stark contrast to the more scientific/biomedical approach, which often tries to locate and isolate a single compound responsible for an herb’s medicinal effects. The problem with this approach is because medicinal plants heal not because of one chemical but because of how all their constituents work together in harmony. This harmony is generally referred to as constituent or whole plant synergy.

The concept of constituent synergy is crucial in herbal medicine because it recognizes the complexity of a plant’s biochemical profile and our human biochemical nature. When we consume a medicinal herb, the plant’s constituents interact with our enzymes, liver metabolism, and circulation, transforming into new substances throughout the process. It’s impossible to fully understand the biochemical changes that occur when ingesting a whole herb, even if we isolate a single constituent.

An excellent example is curcumin in Turmeric (Curcuma longa). Turmeric has been famed for a long time for its anti-inflammatory properties, which are scientifically attributed to curcumin. This constituent is called the “active” constituent of the plant, which implies that the remaining constituents in Turmeric are inactive or unnecessary. In other words, attributing the healing power of Turmeric to the presence of curcumin suggests that the remaining compounds in the plant don’t do anything.

Amidst the Turmeric craze, it was discovered that curcumin alone is poorly absorbed and not very effective. To fix this, supplement companies added other extracts, such as Black Pepper (Piper nigrum) extract—called “bioperine”—, to improve its efficacy and absorption. So they take curcumin out of Turmeric and concentrate, and then have to add something else in order to get it to even absorb into the body. However, when using the whole Turmeric plant—such as in a Turmeric tea with milk or a Turmeric tincture (I.E. a whole plant extract)—curcumin is well absorbed due to the constituent synergy of the whole plant.

While Turmeric is a well known example, the concept of constituent synergy applies to all medicinal plants. In essence, whole plant extracts capture the entire constituent synergy and work together in harmony to deliver the plant’s medicinal virtues in the most balanced way possible. This is in my opinion, honoring the medicine within a plant and using it the way nature intended it to be.

Standardized Extract

Another type of herbal extract you’ll find on the market is the “standardized extract.” This type of extract sits between whole plant extracts and phytopharmaceuticals. They are essentially whole plant extracts that have been adjusted to contain a specific percentage of bioactive constituents. These “spiked” constituents are usually those that have been well studied and shown to have specific desired medicinal actions within the herb.

For example, a Kava-Kava (Piper methysticum) tincture might be regulated so each bottle contains the same percentage of kavalactones. Similarly, Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) extracts are standardized to contain a consistent percentage of ginkgolides, or Saw Palmetto (Serenoa repens) extracts to a uniform percentage of sterols.

Companies produce standardized extracts based on scientific research that shows that certain constituents in a plant provide medicinal effects when taken at specific concentrations. Sometimes herbal formulators creating standardized extracts supplement their products with standardized compounds to ensure consistency in all of their products.

This consistency assures you of the same level of concentration and quality every time you purchase the product, regardless of the season or batch. As herbalists, we want reliability and consistency in our medicines, and standardizing products provides that reliability. This doesn’t mean a non-standardized whole plant extract isn’t reliable, but in some cases, standardized extracts can be more effective whereas a whole plant extract isn’t.

A good example of this is Ginkgo. This was a major fad herb many years ago, becoming quite famous for its ability to enhance cognitive function, stimulate cerebral circulation, and proved a promising remedy for memorgy and cognitive issues in the elderly and for diseases such as Alzheimers and dementia. But, contrary to popular belief, whole plant extracts of Ginkgo leaf really don’t work well for this usage. All of the research done on Ginkgo was done with super concentrated 50:1 extracts to ensure a high concentration of the ginkgolides. To clarify, that’s a 50:1 extract. Consider, most whole plant extracts of dried plants are around 1:5, and fresh herbs are usually around 1:2. A 1:5 Ginkgo leaf tincture is literally an entirely different medicine than the standardized super-concentrated extract.

Do you need to make such powerful concentrations of herbs to get results? Sometimes, as with Ginkgo, it is. However, for many medicinal plants, a typical 1:5 ratio tincture for dried plant material or a 1:2 for fresh is strong enough to help you achieve the results you’re looking for. There are of course exceptions to this general rule of thumb. Last but certainly not least with Ginkgo, is that the leaf is NOT a traditional medicine. In Chinese medicine, the nut was used, but more as a respiratory remedy, not for cognitive function. Using the leaf is a novel way to utilize this medicine, and is solely based on science and super concentrating it.

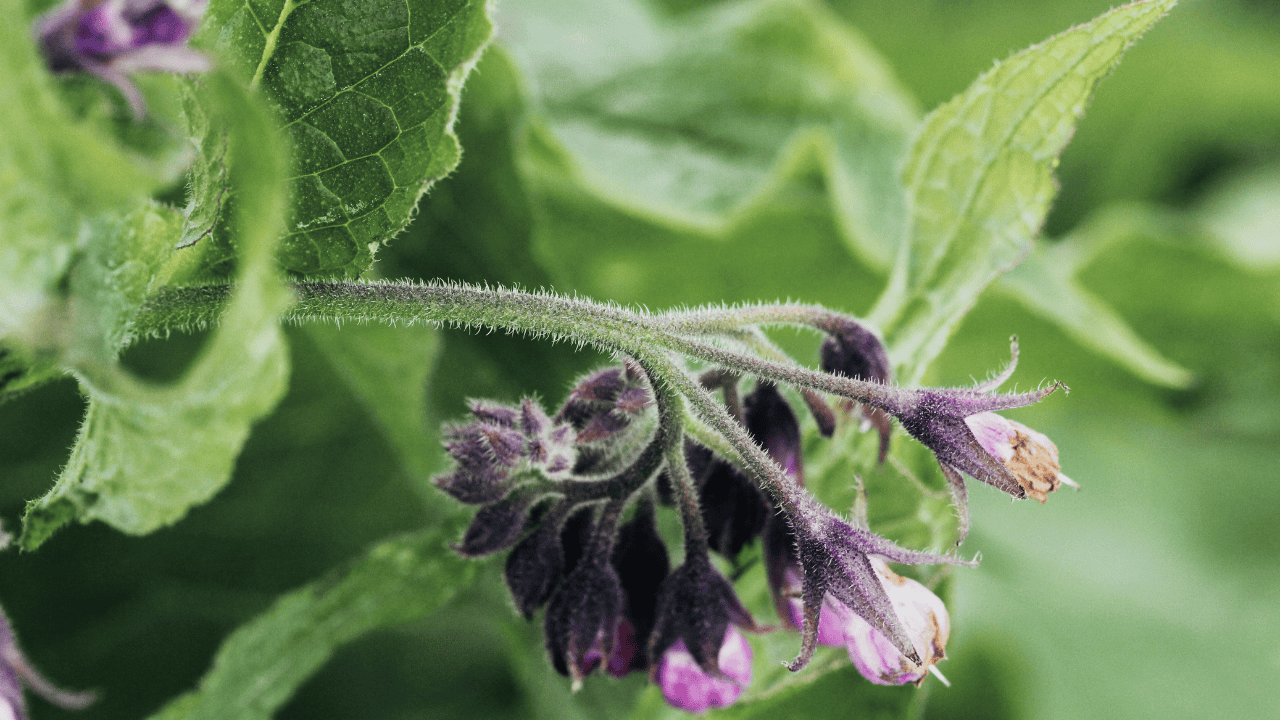

Aside from increasing the percentage strength of certain compounds, it’s also possible to remove harmful compounds when making standardized extracts. For example, certain countries offer Comfrey (Symphytum officinale) extracts free of pyrrolizidine alkaloids, making them safer to consume. Similarly, deglycyrrhizinated Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) has glycyrrhizin removed to avoid raising blood pressure, making it safe for those with hypertension to take.

Standardized extracts provide a reliable and consistent option for those seeking a specific medicinal effect from an herb that only becomes available in certain percentages. By making sure that every batch contains a uniform percentage of bioactive constituents, standardized extracts offer predictability and efficacy, particularly for herbs that may not be as effective in their whole plant form. Super concentrates and the removal of harmful compounds can also improve the efficacy and safety of certain herbs. While standardized extracts (and super concentrates) may not always be needed, they play a crucial role in herbalism when the right herb and situation calls for it, though for the most part, they remain outside the capacity of the home medicine maker to prepare, making us reliant on supplement companies and their products.

Phytopharmaceuticals

The last class of herbal extracts is phytopharmaceuticals, where isolated compounds or complexes of compounds are extracted so they can be administered separately from the rest of the plant.

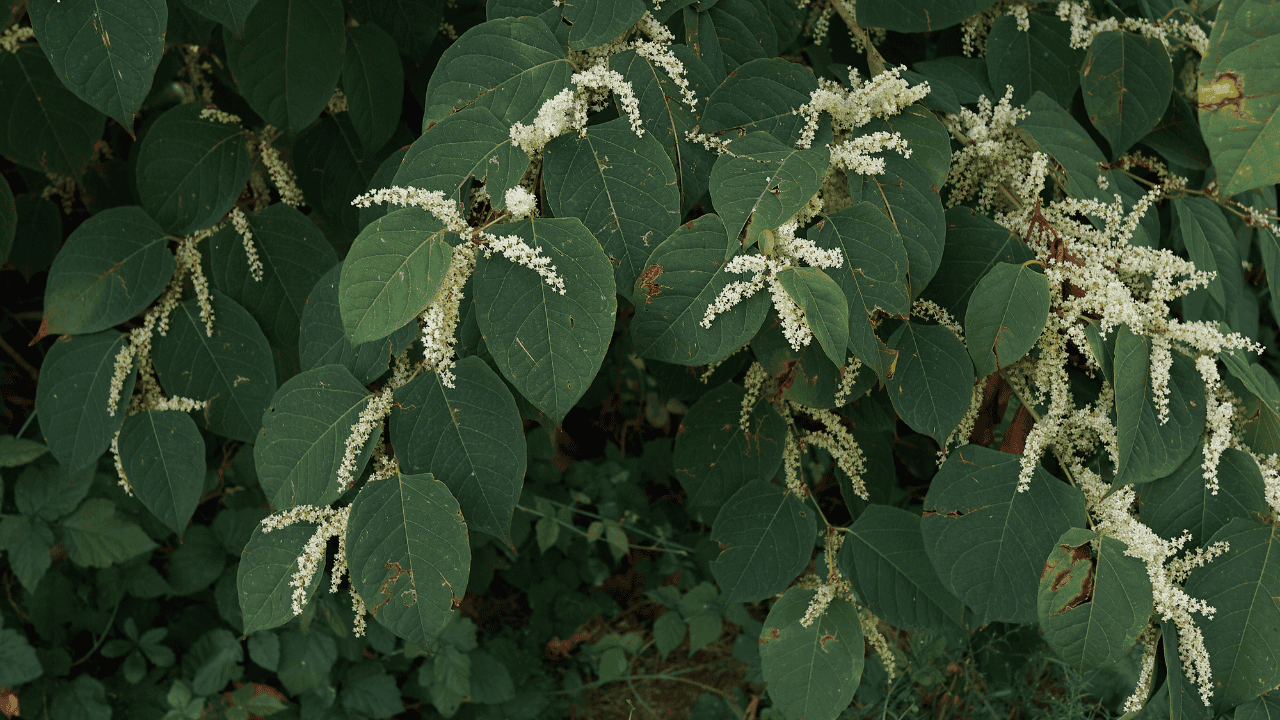

Phytopharmaceutical plant extracts are the closest to a drug you can get in terms of plant extracts. The process of making this type of extract involves isolating specific compounds from the whole plant. Some common examples include Boswellic acid from Frankincense (Boswellia sacra), curcumin extracts from Turmeric, CBD extract from Cannabis, resveratrol from Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) and silymarin from Milk Thistle (Silybum marianum).

Phytopharmaceuticals can be incredibly effective, sometimes offering life-saving benefits where modern medicine falls short. For instance, in some European countries, silymarin from Milk Thistle is often administered as an injectable when someone ingests lethal substances such as the Death Cap mushroom (Amanita phalloides), literally saving their life.

Currently, we don’t even have a western medication that parallels the life saving properties that silymarin has. In such cases, the silymarin phytopharmaceutical is injected with a high potency level that wouldn’t be possible to get from simply taking Milk Thistle tincture. As you can see, phytopharmaceuticals have the potential to be life saving in the right circumstances.

Does that make them better than whole plant or standardized extracts? In some instances yes, and in others, no. I think the key to understanding phytopharmaceutical is that they are very targeted and will not work the same as the whole plant. True, they’ll do something the whole plant does, and perhaps at lower doses and more quickly (due to their concentration). But they will lack the whole plant constituent synergy, and because of this will likely be missing some properties we commonly attribute to the whole plant.

Which Extract Is Best?

With all this said, is there one type of extract that’s better than all the rest? For example, if someone needs general liver support, is a silymarin phytopharmaceutical better than a whole plant extract of Milk Thistle? Or if someone needs antioxidant protection from resveratrol, is taking straight resveratrol better than a Japanese Knotweed extract?

I think it all really depends on the situation, the person, and what’s ailing them. In general, I don’t believe stronger or more concentrated herbal extracts are inherently better or even necessary. Rather, different scenarios call for different extracts. One downside of using plant isolates is poor absorption, which can happen when a compound is separated from the rest of its constituent synergy. Isolates can also be less effective compared to whole extracts, as the latter maintain the natural balance and interaction of all the plant’s constituents. This concept is similar to ecology—removing a keystone species can disrupt the entire ecosystem, potentially causing degradation or collapse. Simply put, things don’t work the same when you divide them in parts.

Because of their holistic nature, whole plant extracts are generally superior, except in certain cases where scientific evidence shows that standardized super concentrates, like Ginkgo, are needed in order for them to work. They can also be better to use in severe cases where strong interventions are needed to provide relief in acute scenarios. However, for general health maintenance, disease prevention, and treatment, whole plant extracts are usually effective enough, offering the added benefits of improved absorption, constituent synergy, and fewer side effects.

Standardizing herbal medicine keeps production reliable, but in that process something is lost. When we separate parts from the whole, we lose the vital intelligence, unique constituent profile, and the secondary metabolites that the plant produced in response to environmental stress. Ultimately, approaching herbal medicine purely from a pharmaceutical model weakens the holistic synergy that whole plant extracts offer. Every kind of herbal extract has its place, but there’s an unparalleled holistic synergy that occurs with whole plant extracts.

The scientific mindset divides wholes into parts to understand them better, and the approach to preparing herbal medicine is no different. Unfortunately, those parts aren’t usually put back together into that wholeness. The alchemical tradition on the other hand does precisely that. While there is crude division that occurs in alchemical pharmacy, as the plant is separated into its Sulfur, Mercury and Salt (volatile constituents, alcohol/water soluble constituents, alkali minerals), it goes a step further by recombining those parts to preserve the whole. To treat the whole person, we need to use a whole medicine, and that’s where whole plant extracts come in, and in my experience, the alchemically prepared spagyrics take the concept of whole plant extract to an entirely new level.

Sometimes it seems that science tries to outsmart nature and believes we can improve upon what is already perfect. The plant, with its natural shape, chemistry, taste, and smell, is inherently perfect. By tinkering with the chemistry of a plant, making isolates, and super concentrates, we can lose out on the synergy that occurs when the plant arrives in nature, perfectly whole and ready to use as is. By learning to harness the holistic nature of the plant, we are better able to support the wholeness of a person and their healing journey.