Herbal medicine is and has always been, the people’s medicine.

Just as there’s significant variation in the people and cultures that fill our world, there’s a myriad of medicine-making techniques that reflect these differences.

What are some traditional forms of medicine making and how do they compare to today’s more “scientific” approaches to herbal pharmacy? Furthermore, is there one that’s better than the rest?

In today’s topic, we’ll be discussing:

- How formulating herbal medicine is a practice as nuanced as the development of herbalism itself

- The ancient, modern, spiritual, and medical practices that all offer unique pathways to healing and their medicine making methodologies

- The pros and cons of taking a standardized approach to medicine-making versus taking a more personal approach

- The unique aspects that each tradition specializes in

- How to identify the best medicine making practice for yourself

Table of Contents

Medicine Making Throughout the Years

Out with the old and in with the new.

That’s the saying, anyway.

But does this apply to preparing herbal medicines? With practices dating back to Mesopotamia, are our current medicine-making techniques superior, more precise, and overall preferred to older methods? How do the more scientifically oriented approaches to extracting plants compare to the older, yet time tested methods?

Rather than asking which tradition offers the best practice for formulating herbal medicine, a question you might ask yourself is “what herbal destination or result do I have in mind, and which road will take me there?”

Folk Practice

One of the oldest traditions in herbalism is to quite literally eat your medicine; to familiarize yourself with the lush expanse that surrounds you and to pick the berries, leaves, and other edible plant parts that can be easily incorporated into your cooking.

Although the potency of most of these medicinal plants is quite low, this is precisely what allows us to eat copious amounts of them while bolstering our health. For example, you can freely pile that Nettle pesto onto your toast without worrying about eating too much of it.

Developing a relationship with nature that is built off learning the seasonal plants, harvesting them intentionally, and using them in the kitchen fosters an intimacy that can’t be bought from an herbal shop or read about in a book . It also lends itself towards developing a profound knowledge of the plant world that is learned through kinesthetic and sensory experience.

Cooking herbs into medicinal broths, infusions, and decoctions were all universally practiced forms of medicine across the world. With 95% proof alcohol not yet available on the market, wine became a humble substitute used for fermenting herbs. We can see this illustrated with the usage of medicinal wines that Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ayurveda both share.

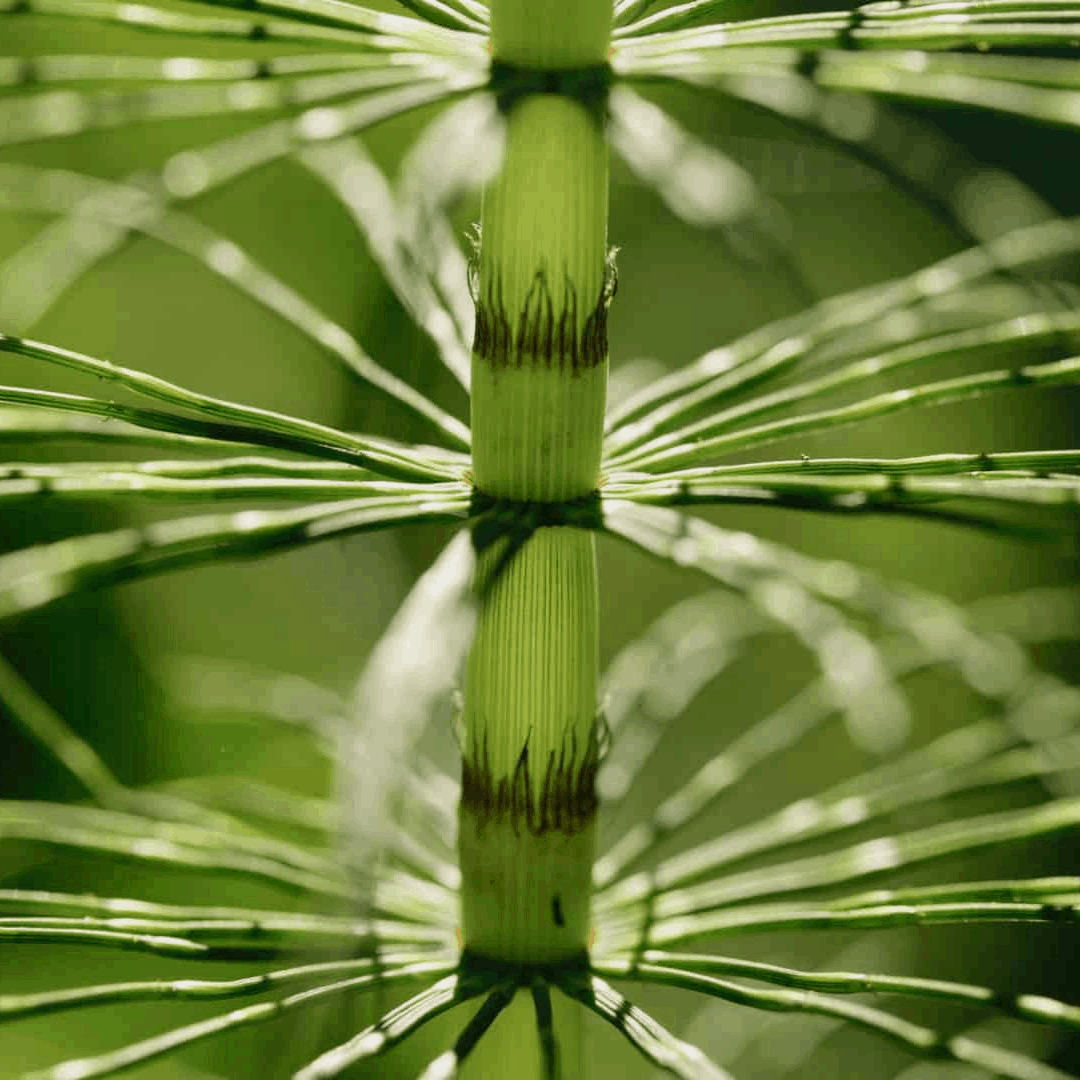

What these all share in common is that they are based on extracting the medicinal components of plants with water, which I like to consider the “universal solvent.” Water is life, and inherently contains within it the intelligence to draw out the core medicinal virtues of most plants.

To clarify a small point, an infusion is simply pouring boiling water over lighter or aromatic plant parts and allowing it to steep for 15-20 minutes. A decoction is actively boiling denser plant parts (like roots and barks) in water for anywhere between 30 minutes and a whole day.

One of the main issues with water based extracts is that they do not preserve well, hence the development of fermented extracts like wines, which then led to further refinement of alcohol and thus the creation of herbal tinctures. It is said that in European herbalism, this was strongly influenced and developed by the alchemical tradition.

Alchemical Work

One of the great gifts born of the alchemical movement was the production of spagyric medicine, and with it, an entirely new way of preparing plants that has ultimately led to more scientifically refined methods of extraction. With an emphasis on utilizing every part of the plant in a way that potentiates its larger whole, spagyricists refined their medicines until the greatest level of the physical and spiritual potency of the plant was achieved.

By using the entire plant to make herbal medicine, spagyricists aim to honor and support the entire ecosystem that lives within a person; in mind, body, and soul. This is achieved through specific processes that extract what is referred to as the Salt, Mercury, and Sulfur of the plant, or its body, spirit and soul.

Although this work is fueled with spiritual insight, the formulaic process used with making spagyrics is not for the light of heart. It requires precision, focus, and concentration in a way that might even resemble modern lab work to some. However, one of the key distinctions between more scientific methods of extraction and alchemical methods, is that the latter concentrates the physical, energetic, AND spiritual properties of the plants. This makes them (in my opinion) one of the most potent and powerful forms of herbal medicine. Ultimately alchemy was the root of iatrochemistry, which later turned into the practice of chemistry, and into modern pharmacology, with a gradual de-spiritualizing of the system of alchemy into a strictly scientific approach.

The Eclectic Movement

With our current phytopharmaceutical industry today, it’s not difficult to isolate medicinal constituents in a plant to create an isolated product. However, this didn’t stop folks from the eclectic herbal movement in the 1800’s- early 1900’s from trying their hand at this – and achieving great success.

Eclectic physicians during that time were highly influenced by new forms of herbal extracts developed by a man named John Uri Lloyd, who was a notable figure that made great strides in distilling plant medicine and concentrating plants to yield specific actions. These herbal extracts were referred to “specific medications,” which was aligned to their method of “specific diagnosis,” developed by the physician John Scudder. This ultimately saved the Eclectic school of medicine which was at the time facing a sort of identity crisis and established it as a valid model of medical practice.

Although the practitioners of this movement did not have the same access to modern technology we have today, they developed their own techniques to reach similar results and the success of their work is a testimony to the curiosity and devotion they brought to their craft. While their specific medications were not necessarily simple herbal tinctures, they also were not nearly as refined as isolated plant extracts we see in modern herbal medicine.

Standardizing Herbal Medicine

With an emphasis on consistency, potency, and efficacy, many medical herbalists place these values as the epicenter of their medicine-making practice.

As a result, using high-proof content alcohol along with other measured agents and a set protocol has become a technique favored by many. This is primarily done by standardizing the percentage of alcohol used to extract the plant, and the particular ratio of grams of herb to ml alcohol. This approach enables the practitioner to know precisely how much of an herb is being delivered per dose. This is particularly important when using low dose botanicals such as Lilly of the Valley (Convallaria majalis), Poke (Phytolacca decandra), and Foxglove (Digitalis purpurea).

For example, in a 1:2 ratio tincture, for every 2 ml of tincture taken, they get 1 gram of herb. So if you want them to get 2 grams per dose, they would take 4 ml of herb. Although many herbal companies employ this strategy to produce large quantities of a consistent and reliable product, there are also home herbalists who love following this method for their own practice.

The other level of “standardizing herbal medicine” is in the form of manufactured products referred to as “standardized extracts.” These more industrially and scientifically prepared medicines focus on isolating and concentrating specific active constituents in the plant that have been studied and shown to have pharmacologically active medicinal properties.

These are often beyond the scope of most practitioners and home medicine makers, as the methods of extraction involve fancy (and likely expensive) equipment to not only prepare, but chemically measure the product. These forms of extract are commonly used by naturally oriented physicians, Naturopaths, and some clinical herbalists.

Indigenous Traditions

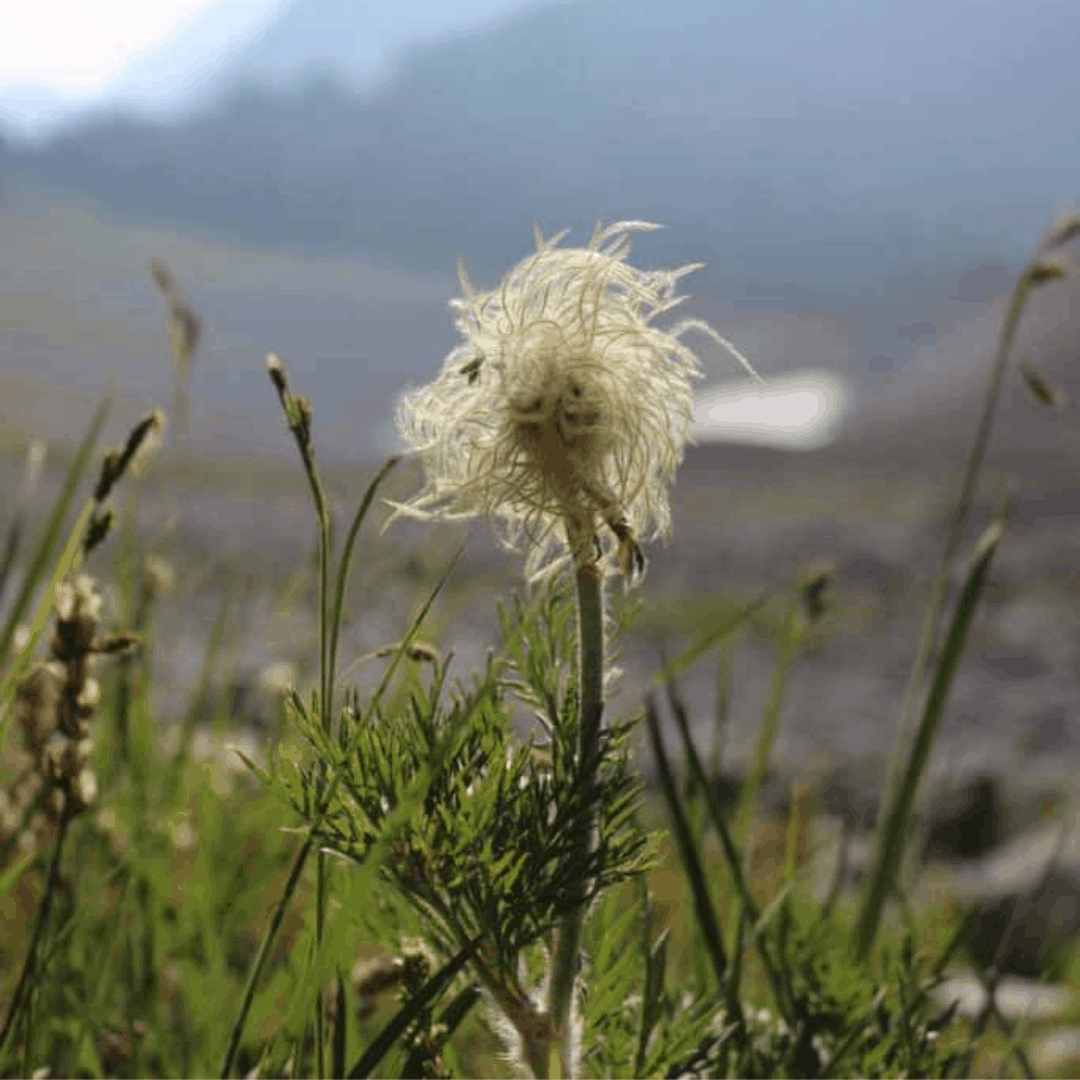

With an emphasis on the spiritual side of nature and the divine breath that runs through people and plants, many traditional healers would not pick an herb or prepare a medicine until they’ve met the person in need of help.This is because many would not keep a stockpile of dried herbs or bottled preparations on hand, but rather preferred to pick the specific plant that was suited to the person needing help. And by specific plant, I don’t just mean the species, I really mean, the specific plant that matched the signature of the person.

After speaking, it was common practice for the healer to identify which plant medicine was in need and then intentionally gather the plants for its preparation; all the while holding a prayer for the specific person in mind.

With such an intentional process, we might better understand why some folks feel that cultivating or harvesting an herb when it’s in season and simply bottling it up for future use is a reductionist way of working with plant medicine. Many see it as disrespecting the spirit of the plant to “trap it in a bottle.”

Besides for crafting an herbal medicine with the intention of a single individual in mind, there are other factors that a traditional healer might take into account. For example, is the Dandelion growing in the shade near a babbling brook on the southside of a hill, or is it blooming in direct sunlight on a northern mound?

It’s common for them to see the environment and location where the plant grows as subtly changing its properties. Another may be using a specific part of the plant that matches the person, for example, harvesting a Mullein flower on the same area of the flowering stalk as the part of the spine that is in pain.

These are factors that may be overlooked in the modern medicine-making process. After all, Matricaria chamomilla (Chamomile), is the same flower any way you slice it, right?

To the modern practitioner, a common response might be “yes.” To the indigenous healer, the elements that surround these plants imbue spiritual energy that may indicate for them to be used in completely different ways.

They have an awareness and acuity of perception of how plants heal that many of us modern folk just simply don’t have, or have lost. Luckily, many of us are rediscovering these levels of specificity in how we work with our plants and are working hard to restore our relationship with them and understanding of their spiritual properties alongside their physical attributes.

Intention As the Foundation for Medicine-Making

Whether you’re a budding herbalist preparing a humble glycerite in your kitchen or a medically inclined practitioner calculating a new herbal formula, there’s one common factor shared in every medicine-making tradition; and that’s in being precise with intention.

If you’re a folk herbalist, you may not be as concerned with the exact percentages and measurements you’re using when medicine-making, but the intention you have while working with the plant may be sublime and the most important part of the process.

As a medical herbalist, your precision may lay in the strategic process you follow when formulating medicine and the specific ratio of herb to menstruum in your extracts.

There is an element of intention and precision that lives within every herbal tradition and the medicine-making techniques they share.

Each containing unique strengths and differences, they all provide healing for ourselves and the community we serve. Rather than trying to seek the “best” one, consider which one you feel most drawn to exploring and follow the road that will take you there.

When laying out your tools and herbs needed for your plant path, pull up a chair, remembering that at the table of herbalism, there’s a seat for everyone.